Excerpts from Educational Horizons, the Official Publication of Pi Lambda Theta

Here's a[n]… author - controversial, exciting, full of conflict, scholarly—whose books are destined to become classics.

By James Briggs

What makes a young adult novel popular? What makes it controversial? What makes it good? Romance, suspense, generational conflict, a rebel-victor at the center, an identity crisis? Realizing that the students will be the ones to answer these questions, I asked a few to react to two recent novels by a … southern writer, Luke Wallin …my impressions and my students' responses suggest that his name is due for greater recognition.

Wallin's first novel, The Redneck Poacher's Son, appeared in 1981. His… most remarkable, published in 1984, is In the Shadow of the Wind. Although each has a singular individuality, the two works are knit by several striking parallels. Each has as its protagonist a tormented sixteen-year-old boy who must overcome personal loyalties to break free of a sinister environment. In both stories there is a girl, sympathetic and supportive; a trusted elder; a threatening tyrant. Most noteworthy is the colorful and authentic setting, the inland Southeast, wherein Wallin frames events from two different centuries.

The Redneck Poacher's Son is a present-day family drama of suspicion, depravity, and deceit. Jesse Watersmith, the central character, lives with his father and two older brothers in the stifling center of a Georgia swamp. Twaint, the father, habitually abuses his children, his neighbors, the wildlife, the land itself. His livelihood is hunting. He passionately declares, "I dream about the deer every night. If I live a hundred years, I won't kill enough of 'em." However, Twaint's hunting is not the rustic pursuit of wild game, but the lawless destruction of whole herds of deer, the indiscriminate trapping of protected species, and even the netting of dead, contaminated fish for sale to "colored" cafes. He also runs moonshine, and there are rumors that men have sickened and even died on Watersmith whiskey. When "Paw" isn't working, he's getting drunk, paying off the sheriff, assaulting and crippling his sister-in-law, Jesse's Aunt May, or extorting money from his sons. The older boys, Robert Elmer and Bean, have at last matured enough to repel Paw's beatings but have otherwise willingly accepted his lifestyle.

It is from this ssqalid background that Jesse must escape. Love of the land and its wildlife, deepening revulsion at Paw's malice, growing awareness of a decent, companionable world just outside his grasp, and haunting skepticism surrounding his mother's drowning when he was only four—all furnish credible, sensible motivation for Jesse's imminent rebellion. A plausible combination of circumstances give him his chance: Will Evans, a lumberman in a nearby town, offers sawmill jobs to the Watersmith boys and even to Paw, an unusually charitable gesture, because Evans had been a victim of Twaint's rancor in the past. Twaint senses profit and consents, and Jesse is happy to detach himself from his family and live in town with Miss Elmilly, a distant relative.

Jesse's hope begins to flourish in this new setting. He lives in a house with a bathtub and his own room; he goes to school; he has spending money. His employer encourages and befriends him, and Evans' pretty daughter, Ren, is quick to appreciate Jesse's rugged individuality compared to the other kids at school. Yet even here, Jesse cannot find peace. He must endure the constant nearness of Paw and buffet the menacing intrusions of his brothers, who always manage to drop by to include him in a drinking binge or a KKK meeting. Jesse also finds a friend in Nathan, a black co-worker whose wife speaks in tongues and claims to convey messages from the dead. It is her naming of Tanya, Jesse's late mother, that brings into focus his need for revenge.

It all makes a heady agenda for an adolescent reader: vengeance, bigotry, parricide, spiritualism, all presented without sentiment or sensation. Wallin closes his story with a forceful synthesis of violence and death, reconciliation and hope. It is a satisfying way out.

Several points make The Redneck Poacher's Son a readable, discussable novel for young readers. First, and most attractive is the tight, quickly paced story line. Many contemporary novels aimed at young adults focus so sharply on the developing personality of the protagonist that the story itself becomes stagnant or unwieldy. But the themes of Jesse's growth never overpower the events nor diminish them. The simple, predictable interaction increases in complexity and originality with each turn of the page.

Students and teachers might be surprised and occasionally shocked by the society Wallin describes. In the modern Southeast, do some teenagers really live in tents deep inside fetid swamps? Can teenagers reach high school age without ever attending school? Are there secret moonshine stills tucked away in remote rural areas? Is there money to be made by supplying gunny sacks of tainted or illegal fish and game through the back doors of sleazy cafes? Can Bible Belt fundamentalism swing wide enough to uphold Ku Klux Klan doctrine and also blend with the folklore of Negro voodoo traditions? And may a family of venomous Klansmen swagger through 246 pages of dialogue without ever cussing or saying "nigger?" Who knows? But all of this encourages thought and reaction and occasionally controversy.

Early reviews of The Redneck Poacher's Son compared Jesse Watersmith to Billy Budd. Although Herman Melville is not generally read in great depth by secondary students, just for fun I asked two of my students to read and react to the comparison. The good but imperfect nature of the two heroes was the obvious starting point. The two youths are clean and well-formed, honest, and recognizably superior to their surroundings. The fatal flaw in both (setting aside Billy's stammer) is a tendency toward violent, if righteous, anger. In contrast with Billy's spontaneous rage against Claggart, Jesse's fatal blow is contemplated but never struck. Melville's Captain Vere, who reluctantly condemns the innocent Budd and is forever after haunted by his action, plays a role similar to that of Will Evans, the long-suffering benefactor of the Watersmiths. Evans brings Jesse to a new environment and a new life, becomes his unofficial guardian, and eventually must exercise a degree of censure when Twaint (not Jesse) betrays his trust. Following Jesse's move to town and Billy's impressment aboard the Indominable, there rises up an ugly shadow of conspiracy in which neigher young man will be a party but which threatens both in the extreme. Finally, there is the protective alliance of Nathan with Jesse to be compared to the oracular presence of Dansker in Billy Budd.

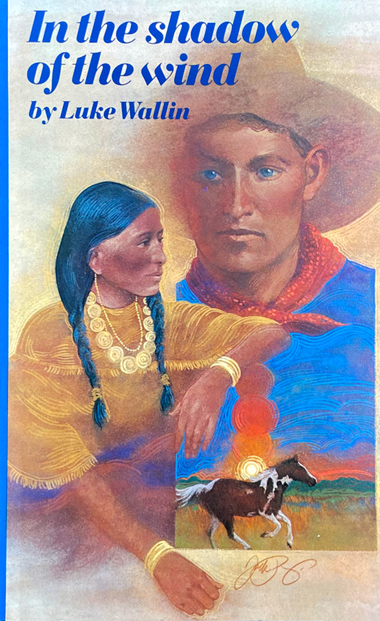

Luke Wallin's … novel, In the Shadow of the Wind, is set in an arena where intercultural conflict reached holocaust proportions—the Creek Wars of the American Southeast in the early nineteenth century. This is much more than a frontier story. Wallin's scholarship is accurate and impressive: he writes with the authority and deep feeling of a native son.

The Creek Confederacy once reigned over most of what is now Alabama, Georgia, and northern Florida. As the inexorable American westering began, treaties were made, broken, readjusted, and made again. This was the era of Andrew Jackson, the Great White Father in Washington; the period of the Great Removal; the years preceding the Trail of Tears when southern woodland tribes were marched en masse to Memphis and across the Great River into the new Indian territory of Oklahoma. Wallin's tale is unsettling to students. It captures the despair of the peace loving Creeks as they cling desperately to their tribal identity. Their plight is embodied in Brown Hawk, an ancient chieftain who must feed his starving people, placate the greed of white plunderers, contain belligerent elements among his own warriors, interpret for his followers the complex issue of slavery, and somehow address the alien concept of individual land ownership in the white man's courts.

Brown Hawk's greatest sympathizer is his grand-niece Pine Basket, from whose perspective many of the tragic events are seen. Pine Basket is just 16, but the disintegration of her culture has touched her in many personal ways. She has seen her community of Foxbluff betrayed by a white missionary, her father and brother embittered, and her mother debilitated by their discouragement. The young brave who will claim her as a bride has become a warlike renegade, and her entire nation has been victimized by marauding settlers. Through it all, she has witnessed the stoic suffering of her uncle Brown Hawk.

Parallel to Pine Basket's story is that of young Caleb McElroy, also 16, whose nearby cabin has already come under violent attack by hostile Creeks. With his mother and grandfather he is squatting in the Alabama woodlands just long enough to fulfill a timber contract. A meeting between Caleb and his grandfather and Brown Hawk and Pine Basket is a pivotal point. It gives the youthful protagonists a first glimpse of each other, underscores early the pitiable desperation of the proud Creeks, and establishes a credible, sustaining trust between the old and young of the two peoples.

The lives of these characters bear the greatest weight in Wallin's diligently constructed plot. In another key development, Six Deer, Pine Basket's brother, will not allow himself to be dissuaded from going on a vision quest to come to terms with his hate. This solitary ritual, not unlike the solemnity described in James Vance Marshall's excellent 1959 novel Walkabout, is an impeccable piece of scholarship. It brings in the inspirational legends of Tecumseh, the grave hazards of austere fasting and overreaching, and even the "black drink" used as a cleansing cathartic prior to the journey. More important, it is Caleb McElroy, strayed from a distasteful wolf hunt, who eventually discovers the unconscious, emaciated, nearly-frozen Six Deer.

This discovery and its aftermath form the basis of the rest of the story. The unlikely savior role of the white settler is a mixed blessing. It draws Caleb into a closer sympathy with the beleaguered Creeks. Brown Hawk offers to cede Indian land directly to him, an act inspired by a holy vision, in the hope of protecting them from white encroachment. But Caleb cannot build a wind shadow around the whole Creek nation as he did around Six Deer to save his life. He now knows too much. Unprincipled frontiersmen, with government approval, force him to lead a raid against the Creeks, promising to do no more than recapture lost property. But promises made to the red man are seldom kept, and soon Caleb finds himself the unwilling destroyer of those he tried to protect.

The third and final phase of the novel brings together not Caleb and Pine Basket as we might expect, but Caleb and Six Deer. Now allies, they must rescue Pine Basket and her mother from white captors, who are driving them to the Great River and beyond. The women are found alive, though they have not been spared the indignities of captivity. In a daring infiltration of a large encampment near Memphis, the two heroes blend force and cunning to free the women and in the process exact a suitable retribution on the tyrants who held them. On this faintly optimistic note, the main story line ends.

In a brief afterward, Wallin writes in almost a liturgical cadence of the years that followed. Caleb and Pine Basket married and became farmers and storekeepers in the new Indian territory of Oklahoma. Later in life, each assume a distinguishing stature. Caleb fought in the Union Army in the Civil War, and Pine Basket became a revered keeper of old secrets, a writer of old songs and memories, a living repository of the traditions of the lost nation.

In the Shadow of the Wind offers several perspectives on American history that are seldom found in school texts. For example, the Creeks were an agricultural people who believed in communal and private ownership of gardens and crops. The welfare of their communities depended as much on these as on hunting and trapping. But the land itself was to be held in common, and it was the parceling of land for the sole use of white planters that led to starvation and hostility, probably in that order. Still, the Creeks were willing to live side by side with Europeans, and there is a long history of negotiation with white settlers and government officials. Nevertheless, there were soon outrageous laws on the books. In a court, no Creek's word would be upheld against that of any white; no white could be effectively prosecuted for crimes against an Indian. In the novel, Little Bear, Pine Basket's father, journeys to Washington to talk with the Great White Father, but his overture meets with neglect and disdain, and he returns demoralized and embittered.

Alcohol abuse is another infamous example of the white man's evil. Though mentioned only briefly in the novel, it is a fact that much Creek land was acquired "legally" over j ust a few years from micos and councilmen plied with liquor.

The greatest white vice, regrettably also adopted by the Creeks was slavery. Many Creek communities did hold black slaves, and it was their presence in white settlements that sometimes led to raiding and pillaging by Indians. But, not even here does Wallin fall into sentimentalism. Though his sympathies are obviously with the dispossessed Creeks, there is abundant good and evil on both sides to weigh and discuss.

Luke Wallin's novels are not thin literature. There is much in them to appeal to the scholar, certainly to the history buff, to the student of Native American culture, to the regionalist, and even to the spiritualist. But Wallin should best be regarded as a fine writer of young adult fiction. It is here that his craft waxes toward genius.

In Nov. 2008 In the Shadow of the Wind was selected a book in common for the Writing for Children and Young Adult area of the Spalding University MFA in Creative Writing Program. Luke met with graduate students and discussed the genesis of the idea, the research, and the process of writing and revising, working with the great editor Richard Jackson of Bradbury Press.

The Redneck Poacher's Son was selected a Best Book by the American Library Association's Booklist.

In the Shadow of the Wind was selected a Best Book by the New York Public Library. It was recommended for history classes by the National Council on American History for the period 1800-1850.

Topics:

⟶ Return to Longing for Wilderness page.